Now I will be taking info from EWTN or some other website because I am not very good at putting together words on my own. :P

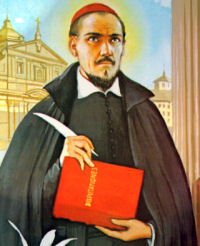

Our first saint is: St. Robert Bellarmine-Feast Day is September 17th

A distinguished Jesuit theologian, writer, and cardinal, born at Montepulciano, 4 October, 1542; died 17 September, 1621. His father was Vincenzo Bellarmino, his mother Cinthia Cervini, sister of Cardinal Marcello Cervini, afterwards Pope Marcellus II. He was brought up at the newly founded Jesuit college in his native town, and entered the Society of Jesus on 20 September, 1560, being admitted to his first vows on the following day. The next three years he spent in studying philosophy at the Roman College, after which he taught the humanities first at Florence, then at Mondovì. In 1567 he began his theology at Padua, but in 1569 was sent to finish it at Louvain, where he could obtain a fuller acquaintance with the prevailing heresies. Having been ordained there, he quickly obtained a reputation both as a professor and a preacher, in the latter capacity drawing to his pulpit both Catholics and Protestants, even from distant parts. In 1576 he was recalled to Italy, and entrusted with the chair of Controversies recently founded at the Roman College. He proved himself equal to the arduous task, and the lectures thus delivered grew into the work "De Controversiis" which, amidst so much else of excellence, forms the chief title to his greatness. This monumental work was the earliest attempt to systematize the various controversies of thetime, and made an immense impression throughout Europe, the blow it dealt to Protestantism being so acutely felt in Germany and England that special chairs were founded in order to provide replies to it. Nor has it even yet been superseded as the classical book on its subject-matter, though, as was to be expected, the progress ofcriticism has impaired the value of some of its historical arguments.

In 1588 Bellarmine was made Spiritual Father to the Roman College, but in 1590 he went with Cardinal Gaetano as theologian to the embassy Sixtus V was then sending into France to protect the interests of the Church amidst the troubles of the civil wars. Whilst he was there news reached him that Sixtus, who had warmly accepted the dedication of his "De Controversiis", was now proposing to put its first volume on the Index. This was because he had discovered that it assigned to the Holy See not a direct but only an indirect power over temporals. Bellarmine, whose loyalty to the Holy See was intense, took this greatly to heart; it was, however, averted by the death of Sixtus, and the new pope, Gregory XIV, even granted to Bellarmine's work the distinction of a special approbation. Gaetano's mission now terminating, Bellarmine resumed his work as Spiritual Father, and had the consolation of guiding the last years of St. Aloysius Gonzaga, who died in the Roman College in 1591. Many years later he had the further consolation of successfully promoting the beatification of the saintly youth. Likewise at this time he sat on the final commission for the revision of the Vulgate text. This revision had been desired by the Council of Trent, and subsequent popes had laboured over the task and had almost brought it to completion. But Sixtus V, though unskilled in this branch of criticism, had introduced alterations of his own, all for the worse. He had even gone so far as to have an impression of this vitiated edition printed and partially distributed, together with the proposed Bull enforcing its use. He died, however, before the actual promulgation, and his immediate successors at once proceeded to remove the blunders and call in the defective impression. The difficulty was how to substitute a more correct edition without affixing a stigma to the name of Sixtus, and Bellarmine proposed that the new edition should continue in the name of Sixtus, with a prefatory explanation that, on account of aliqua vitia vel typographorum vel aliorum which had crept in, Sixtus had himself resolved that a new impression should be undertaken. The suggestion was accepted, and Bellarmine himself wrote the preface, still prefixed to the Clementine edition ever since in use. On the other hand, he has been accused of untruthfulness in stating that Sixtus had resolved on a new impression. But his testimony, as there is no evidence to the contrary, should be accepted as decisive, seeing howconscientious a man he was in the estimation of his contemporaries; and the more so since it cannot be impugned without casting a slur on thecharacter of his fellow-commissioners who accepted his suggestion, and of Clement VIII who with full knowledge of the facts gave his sanction to Bellarmine's preface being prefixed to the new edition. Besides, Angelo Rocca, the Secretary of the revisory commissions of Sixtus V and the succeeding pontiffs, himself wrote a draft preface for the new edition in which he makes the same statement: (Sixtus) "dum errores ex typographiâ ortos, et mutationes omnes, atque varias hominum opiniones recognoscere cœpit, ut postea de toto negotio deliberare atque Vulgatam editionem, prout debebat, publicare posset, morte præventus quod cœperat perficere non potuit". This draft preface, to which Bellarmine's was preferred, is still extant, attached to the copy of the Sixtine edition in which the Clementine corrections are marked, and may be seen in the Biblioteca Angelica at Rome.

In 1592 Bellarmine was made Rector of the Roman College, and in 1595 Provincial of Naples. In 1597 Clement VIII recalled him to Rome and made him his own theologian and likewise Examiner of Bishops and Consultor of the Holy Office. Further, in 1599 he made him Cardinal-Priest of the title of Santa Maria in viâ, alleging as his reason for this promotion that "the Church of God had not his equal in learning". He was now appointed, along with the Dominican Cardinal d'Ascoli, an assessor to Cardinal Madruzzi, the President of the Congregation de Auxiliis, which had been instituted shortly before to settle the controversy which had recently arisen between the Thomists and the Molinists concerning the nature of the concord between efficacious grace and human liberty. Bellarmine's advice was from the first that the doctrinal question should not be decided authoritatively, but left over for further discussion in the schools, the disputants on either side being strictly forbidden to indulge in censures or condemnations of their adversaries. Clement VIII at first inclined to this view, but afterwards changed completely and determined on a doctrinal definition. Bellarmine's presence then became embarrassing, and he appointed him to the Archbishopric of Capua just then vacant. This is sometimes spoken of as the cardinal's disgrace, but Clement consecrated him with his own hands--an honour which the popes usually accord as a mark of special regard. The new archbishop departed at once for his see, and during the next three years set a bright example of pastoral zeal in its administration.

In 1605 Clement VIII died, and was succeeded by Leo XI who reigned only twenty-six days, and then by Paul V. In both conclaves, especially that latter, the name of Bellarmine was much before the electors, greatly to his own distress, but his quality as a Jesuit stood against him in the judgment of many of the cardinals. The new pope insisted on keeping him at Rome, and the cardinal, obediently complying, demanded that at least he should be released from an episcopal charge the duties of which he could no longer fulfil. He was now made a member of the Holy Office and of other congregations, and thenceforth was the chief advisor of the Holy See in the theological department of its administration. Of the particular transactions with which his name is most generally associated the following were the most important: The inquiry de Auxiliis, which after all Clement had not seen his way to decide, was now terminated with a settlement on the lines of Bellarmine's original suggestion. 1606 marked the beginning of the quarrel between the Holy See and the Republic of Venice which, without even consulting the pope, had presumed to abrogate the law of clerical exemption from civil jurisdiction and to withdraw the Church's right to hold real property. The quarrel led to a war of pamphlets in which the part of the Republic was sustained by John Marsiglio and an apostate monk named Paolo Sarpi, and that of the Holy See by Bellarmine and Baronius. Contemporaneous with the Venetian episode was that of the English Oath of Alliance. In 1606, in addition to the grave disabilities which already weighed them down, the English Catholics were required under pain of prœmunire to take an oath of allegiance craftily worded in such wise that a Catholic in refusing to take it might appear to be disavowing an undoubted civl obligation, whilst if he should take it he would be not merely rejecting but even condemning as "impious and heretical" the doctrine of the deposing power, that is to say, of a power, which, whether rightly or wrongly, the Holy See had claimed and exercised for centuries with the full approval of Christendom, and which even in that age the mass of the theologians of Europe defended. The Holy See having forbidden Catholics to take this oath, King James himself came forward as its defender, in a book entitled "Tripoli nodo triplex cuneus", to which Bellarmine replied in his "Responsio Matthfi Torti". Other treatises followed on either side, and the result of one, written in denial of the deposing power by William Barclay, an English jurist resident in France, was that Bellarmine's reply to it was branded by the Regalist Parlement of Paris. Thus it came to pass that, for following the via media of the indirect power, he was condemned in 1590 as too much of a Regalist and in 1605 as too much of a Papalist.

Bellarmine did not live to deal with the later and more serious stage of the Galileo case, but in 1615 he took part in its earlier stage. He had always shown great interest in the discoveries of that investigator, and was on terms of friendly correspondence with him. He took up too--as is witnessed by his letter to Galileo's friend Foscarini--exactly the right attitude towards scientific theories in seeming contradiction with Scripture. If, as was undoubtedly the case then with Galileo's heliocentric theory, a scientific theory is insufficiently proved, it should be advanced only as an hypothesis; but if, as is the case with this theory now, it is solidly demonstrated, care must be taken to interpretScripture only in accordance with it. When the Holy Office condemned the heliocentric theory, by an excess in the opposite direction, it becameBellarmine's official duty to signify the condemnation to Galileo, and receive his submission. Bellarmine lived to see one more conclave, that which elected Gregory XV (February, 1621). His health was now failing, and in the summer of the same year he was permitted to retire to Sant' Andrea and prepare for the end. His death was most edifying and was a fitting termination to a life which had been no less remarkable for its virtues than for its achievements.

His spirit of prayer, his singular delicacy of conscience and freedom from sin, his spirit of humility and poverty, together with the disinterestedness which he displayed as much under the cardinal's robes as under the Jesuit's gown, his lavish charity to the poor, and his devotedness to work, had combined to impress those who knew him intimately with the feeling that he was of the number of the saints. Accordingly, when he died there was a general expectation that his cause would be promptly introduced. And so it was, under Urban VIII in 1627, when he became entitled to the appellation of Venerable. But a technical obstacle, arising out of Urban VIII's own general legislation in regard to beatifications, required its prorogation at that time. Though it was reintroduced on several occasions (1675, 1714, 1752, and 1832), and though on each occasion the great preponderance of votes was in favour of the beatification, a successful issue came only after many years. This was partly because of the influential character of some of those who recorded adverse votes, Barbarigo, Casante, and Azzolino in 1675, and Passionei in 1752, but still more for reasons of political expediency, Bellarmine's name being closely associated with a doctrine of papal authority most obnoxious to the Regalist politicians of the French Court. "We have said", wrote Benedict XIV to Cardinal de Tencin, "in confidence to the General of the Jesuits that the delay of the Cause has come not from the petty matters laid to his charge by Cardinal Passionei, but from the sad circumstances of the times" (Études Religieuses, 15 April, 1896).

[Note: St. Robert Bellarmine was canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1930, and declared a Doctor of the Universal Church in 1931. He is the patron saint of catechists.]

(Taken from Catholic Encyclopedia)

(Taken from Catholic Encyclopedia)

Read more: http://www.ewtn.com/saintsHoly/saints/R/strobertbellarmine.asp#ixzz3YjC7e7qp

Our next saint is: St. Olympias-Feast Day: July 25th

St Olympias, the glory of the widows in the Eastern church, was a lady of illustrious descent and a plentiful fortune. She was born about the year 368, and left an orphan under the care of Procopius, who seems to have been her uncle; but it was her greatest happiness that she was brought up under the care of Theodosia, sister to St Amphilochius, a most virtuous and prudent woman, whom St Gregory Nazianzen called a perfect pattern of piety, in whose life the tender virgin saw as in a glass the practice of all virtues, and it was her study faithfully to transcribe them into the copy of her own life. From this example which was placed before her eyes she raised herself more easily to contemplate and to endeavour to imitate Christ, who in all virtues is the divine original which every Christian is bound to act after. Olympias, besides her birth and fortune, was, moreover, possessed of all the qualifications of mind and body which engage affection and respect. She was very young when she married Nebridius, treasurer of the Emperor Theodosius the Great, and who was for some time prefect of Constantinople; but he died within twenty days after his marriage.

Our saint was addressed by several of the most considerable men of the court, and Theodosius was very pressing with her to accept for her husband Elpidius, a Spaniard, and his near relation. She modestly declared her resolution of remaining single the rest of her days; the emperor continued to urge the affair, and after several decisive answers of the holy widow, put her whole fortune in the hands of the prefect of Constantinople with orders to act as her guardian till she was thirty years old. At the instigation of the disappointed lover, the prefect hindered her from seeing the bishops or going to church, hoping thus to tire her into a compliance. She told the emperor that she was obliged to own his goodness in easing her of her heavy burden of managing and disposing of her own money; and that the favour would be complete if he would order her whole fortune to be divided between the poor and the church. Theodosius, struck with her heroic virtue, made a further inquiry into her manner of living, and conceiving an exalted idea of her piety, restored to her the administration of her estate in 391. The use which she made of it was to consecrate the revenues to the purposes which religion and virtue prescribe. By her state of widowhood, according to the admonition of the apostle, she looked upon herself as exempted even from what the support of her rank seemed to require in the world, and she rejoiced that the slavery of vanity and luxury was by her condition condemned even in the eyes of the world itself. With great fervour she embraced a life of penance and prayer. Her tender body she macerated with austere fasts, and never ate flesh or anything that had life; by habit, long watchings became as natural to her as much sleep is to others; and she seldom allowed herself the use of a bath, which is thought a necessary refreshment in hot countries, and was particularly so before the ordinary use of linen. By meekness and humility she seemed perfectly crucified to her own will and to all sentiments of vanity, which had no place in her heart nor share in any of her actions. The modesty, simplicity, and sincerity, from which she never departed in her conduct, were a clear demonstration what was the sole object of her affections and desires. Her dress was mean, her furniture poor, her prayers assiduous and fervent, and her charities without bounds. These St Chrysostom compares to a river which is open to all and diffuses its waters to the bounds of the earth and into the ocean itself. The most distant towns, isles, and deserts received plentiful supplies by her liberality, and she settled whole estates upon remote destitute churches. Her riches indeed were almost immense, and her mortified life afforded her an opportunity of consecrating them all to God. Yet St Chrysostom found it necessary to exhort her sometimes to moderate her alms, or rather to be more cautious and reserved in bestowing them, that she might be enabled to succour those whose distresses deserved a preference.

The devil assailed her by many trials, which God permitted for the exercise and perfecting of her virtue. The contradictions of the world served only to increase her meekness, humility, and patience, and with her merits to multiply her crowns. Frequent severe sicknesses, most outrageous slanders and unjust persecutions succeeded one another. Her virtue was the admiration of the whole church, as appears by the manner in which almost all the saints and great prelates of that age mention her. St Amphilochius, St Epiphanius, St Peter of Sebaste, and others were fond of her acquaintance and maintained a correspondence with her, which always tended to promote God's glory and the good of souls. Nectarius, Archbishop of Constantinople, had the greatest esteem for her sanctity, and created her deaconess to serve that church in certain remote functions of the ministry, of which that sex is capable, as in preparing linen for the altars and the like. A vow of perpetual chastity was always annexed to this state. St Chrysostom, who was placed in that see in, 398, had not less respect for the sanctity of Olympias than his predecessor, and as his extraordinary piety, experience, and skill in sacred learning made him an incomparable guide and model of a spiritual life, he was so much the more honoured by her; but he refused to charge himself with the distribution of her alms as Nectarius had done. She was one of the last persons whom St Chrysostom took leave of when he went into banishment on the 20th of June in 404. She was then in the great church, which seemed the place of her usual residence; and it was necessary to tear her from his feet by violence. After St Chrysostom's departure she had a great share in the persecution in which all his friends were involved. She was convened before Optatus, the prefect of the city, who was a heathen. She justified herself as to the calumnies which were shamelessly alleged in court against her; but she assured the governor that nothing should engage her to hold communion with Arsacius, a schismatical usurper of another's see. She was dismissed for that time and was visited with a grievous fit of sickness, which afflicted her the whole winter. In spring she was obliged by Arsacius and the court to leave the city, and wandered from place to place. About midsummer in 405 she was brought back to Constantinople and again presented before Optatus, who, without any further trial, sentenced her to pay a heavy fine because she refused to communicate with Arsacius. Her goods were sold by a public auction; she was often dragged before public tribunals; her clothes were torn by the soldiers, her farms rifled by many amongst the dregs of the people, and she was insulted by her own servants and those who had received from her hands the greatest favours. Atticus, successor of Arsacius, dispersed and banished the whole community of nuns which she governed; for it seems, by what Palladius writes, that she was abbess, or at least directress, of the monastery which she had founded near the great church, which subsisted till the fall of the Grecian empire. St Chrysostom frequently encouraged and comforted her by letters; but he sometimes blamed her grief. He bid her particularly to rejoice under her sicknesses, which she ought to place among her most precious crowns, in imitation of Job and Lazarus. In his distress she furnished him with plentiful supplies, wherewith he ransomed many captives and relieved the poor in the wild and desert countries into which he was banished. She also sent him drugs for his own use when he laboured under a bad state of health. Her lingering martyrdom was prolonged beyond that of St Chrysostom; for she was living in 408, when Palladius wrote his Dialogue on the Life of St Chrysostom. The other Palladius, in the Lausiac history which he compiled in 420, tells us that she died under her sufferings and, deserving to receive the recompense due to holy confessors, enjoyed the glory of heaven among the saints.

The saints all studied to husband every moment to the best advantage, knowing that life is very short, that night is coming on apace, in which no one will be able to work, and that all our moments here are so many precious seeds of eternity. If we applied ourselves with the saints to the uninterrupted exercise of good works we should find that, short as life is, it affords sufficient time for extirpating our evil inclinations, learning to put on the spirit of Christ, working our souls into a heavenly temper, adorning them with all virtues and laying in a provision for eternity. But through our unthinking indolence, the precious time of life is reduced almost to nothing, because the greatest part of it is absolutely thrown away. So numerous is the tribe of idlers and the class of occupations which deserve no other denomination than that of idleness that a bare list would fill a volume. The complaint of Seneca agrees no less to the greatest part of Christians than to the idolaters, that "Almost their whole lives are spent in doing nothing, and the whole in doing nothing to the purpose." Let no moments be spent merely to pass time; diversions and corporeal exercise ought to be used with moderation, only as much as may seem requisite for bodily health and the vigour of the mind. Everyone is bound to apply himself to some serious employment. This and his necessary recreations must be referred to God, and sanctified by a holy intention other circumstances which virtue prescribes; and in all our actions humility, patience, various acts of secret prayer, and other virtues ought, according to the occasions, to be exercised. Thus will our lives be a continued series of good works and an uninterrupted holocaust of divine praise and love. That any parts of this sacrifice should be defective ought to be the subject of our daily compunction and tears.

Our last saint is: St. Margaret of Cortona-Feast Day: May 16th

They were stirring times in Tuscany when Margaret was born. They were the days of Manfred and Conradin, of the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy, when passions of every kind ran high, and men lived at great extremes. They were times of great sinners, but also of great saints; Margaret lived to hear of the crowning and resignation of St. Celestine V, whose life and death are a vivid commentary on the spirits that raged throughout that generation. It was the age of St. Thomas in Paris, of Dante in Florence; of Cimabue and Giotto; of the great cathedrals and universities. In Tuscany itself, apart from the coming and going of soldiers, now of the Emperor, now of the Pope, keeping the countryside in a constant state of turmoil, and teaching the country-folk their ways, there were for ever rising little wars among the little cities themselves, which were exciting and disturbing enough. For instance, when Margaret was a child, the diocese in which she lived, Chiusi, owned a precious relic, the ring of the Blessed Virgin Mary. An Augustinian friar got possession of this relic, and carried it off to Perugia. This caused a war, Chiusi and Perugia fought for the treasure and Perugia won. Such was the spirit of her time, and of the people among whom she was brought up.

It was also a time of the great revival; when the new religious orders had begun to make their mark, and the old ones had renewed their strength. Franciscans and Dominicians had reached down to the people, and every town and village in the country had responded to their call to better things. St. Francis of Assisi had received the stigmata on Mount Alverno twenty years before, quite close to where Margaret was born; St. Clare died not far away, when Margaret was four years old. And there was the opposite extreme, the enthusiasts whose devotion degenerated into heresy. When Margaret was ten there arose in her own district the Flagellants, whose processions of men, women, and children, stripped to the waist and scourging themselves to blood, must have been a not uncommon sight to her and her young companions.

Margaret was born in Laviano, a little town in the diocese of Chiusi. Her parents were working people of the place; their child was very beautiful, and in their devotion, for she was the only one, they could scarcely help but spoil her. Thus from the first Margaret, as we would say, had much against her; she grew up very willful and, like most spoilt children, very restless and dissatisfied. Very soon her father's cottage was too small for her; she needed companions; she found more life and excitement in the streets of the town Next, in course of time the little town itself grew too small; there was a big world beyond about which she came to know, and Margaret longed to have a part in it. Moreover she soon learnt that she could have a part in it if she chose. For men took notice of her, not only men of her own station and surroundings, whom she could bend to her will as she pleased; but great and wealthy men from outside, who would sometimes ride through the village, and notice her, and twit her for her beautiful face. They would come again; they were glad to make her acquaintance, and sought to win her favor. Margaret quickly learned that she had only to command, and there were many ready to obey.

While she was yet very young her mother died; an event which seemed to deprive her of the only influence that had hitherto held her in check. Margaret records that she was taught by her mother a prayer she never forgot: "O Lord Jesus, I beseech thee, grant salvation to all those for whom thou wouldst have me pray." To make matters worse her father married again. He was a man of moods, at one time weak and indulgent, at another violent to excess, and yet with much in him that was lovable, as we shall have reason to see. But with the step-mother there was open and continued conflict. She was shocked at Margaret's willfulness and independence, and from her first coming to the house was determined to deal with them severely. Such treatment was fatal to Margaret. As a modern student has written of her: "Margaret's surroundings were such as to force to the surface the weaknesses of her character. As is clear from her own confessions, she was by nature one of those women who thirst for affection, in whom to be loved is the imperative need of their lives. She needed to be loved that her soul might be free, and in her home she found not what she wanted. Had she been of the weaker sort, either morally or physically, she would have accepted her lot, vegetated in spiritual barrenness, married eventually a husband of her father's choice, and lived an uneventful life with a measure of peace."

As it was she became only the more willful and reckless. If there was not happiness for her, either at home or elsewhere, there was pleasure and, with a little yielding on her part, as much of it as she would. In no long time her reputation in the town was one not to be envied; before she was seventeen years of age she had given herself up to a life of indulgence, let the consequences be what they might.

Living such a life it soon became evident that Margaret could not stay in Laviano. The circumstances which took her away are not very clear; we choose those which seem the most satisfactory. A certain nobleman, living out beyond Montepulciano, which in those days was far away, was in need of a servant in his castle. Margaret got the situation, there at least she was free from her step-mother and, within limits, could live as she pleased. But her master was young, and a sporting man, and no better than others of his kind. He could not fail to take notice of the handsome girl who went about his mansion, holding her head high as if she scorned the opinions of men, with an air of independence that seemed to belong to one above her station. He paid her attention; he made her nice presents, he would do her kindnesses even while she served him. And on her side, Margaret was skilled in her art; she was quick to discover that her master was as susceptible to her influence as were the other less distinguished men with whom she had done as she would in Laviano. Moreover this time she was herself attracted; she knew that this man loved her, and she returned it in her way. There were no other competitors in the field to distract her; there was no mother to warn her, no step-mother to abuse her. Soon Margaret found herself installed in the castle, not as her master's wife, for convention would never allow that, but as his mistress, which was more easily condoned. Some day, he had promised her, they would be married, but the day never came. A child was born, and with that Margaret settled down to the situation.

For some years she accepted her lot, though every day what she had done grew upon her more and more. Apart from the evil life she was living, her liberty loving nature soon found that instead of freedom she had secured only slavery. The restless early days in Laviano seemed, in her present perspective, less unhappy than she had thought; the poverty and restraint of her father's cottage seemed preferable to the wealth and chains of gold she now endured. In her lonely hours, and they were many, the memory of her mother came up before her, and she could not look her shadow in the face. And with that revived the consciousness of sin, which of late she had defied, and had crushed down by sheer reckless living, but which now loomed up before her like a haunting ghost. She saw it all she hated it all, she hated herself because of it, but there was no escape. It was all misery, but she must endure it; she had made her own bed, and must henceforth lie upon it. In her solitary moments she would wander into the gloom of the forest, and there would dream of the life that might have been, a life of virtue and of the love of God. At her castle gate she would be bountiful; if she could not be happy herself, at least she could do something to help others. But for the rest she was defiant. She went about her castle with the airs of an unbeaten queen. None should know, not even the man who owned her, the agony that gnawed at her heart. From time to time there would come across her path those who had pity for her. They would try to speak to her, they would warn her of the risk she was running; but Margaret, with her every ready wit, would laugh at their warnings and tell them that some day she would be a saint.

So things went on for nine years, till Margaret was twenty-seven. On a sudden there came an awakening. It chanced that her lord had to go away on a distant journey; in a few days, when the time arrived for his return, he did not appear. Instead there turned up at the castle gate his favorite hound, which he had taken with him. As soon as it had been given admittance it ran straight to Margaret's room, and there began to whine about her, and to tug at her dress as if it would drag her out of the room. Margaret saw that something was amiss.

Anxious, not daring to express to herself her own suspicions, she rose and followed the hound wherever it might lead; it drew her away down to a forest a little distance from the castle walls. At a point where a heap of faggots had been piled, apparently by wood-cutters, the hound stood still, whining more than ever, and poking beneath the faggots with its nose. Margaret, all trembling, set to work to pull the heaps away; in a hole beneath lay the corpse of her lord, evidently some days dead, for the maggots and worms had already begun their work upon it.

How he had come to his death was never known; after all, in those days of high passions, and family feuds, such murders were not uncommon. The careful way the body had been buried suggested foul play; that was all. But for Margaret the sight she saw was of something more than death. The old faith within her still lived, as we have already seen, and now insisted on asking questions. The body of the man she had loved and served was lying there before her, but what had become of his soul? If it had been condemned, and was now in hell, who was, in great part at least, responsible for its condemnation? Others might have murdered his body, but she had done infinitely worse Moreover there was herself to consider. She had known how, in the days past, she had stirred the rivalry and mutual hatred of men on her account and had gloried in it who knew but that this deed had been done by some rival because of her? Or again, her body might have been Lying there where his now lay, her fatal beauty being eaten by worms, and in that case where would her soul then have been? Of that she could have no sort of doubt. Her whole life came up before her, crying out now against her as she had never before permitted it to cry. Margaret rushed from the spot, beside herself in this double misery, back to her room, turned in an instant to a torture-chamber.

What should she do next? She was not long undecided. Though the castle might still be her home, she would not stay in it a moment longer. But where could she go? There was only one place of refuge that she knew, only one person in the world who was likely to have pity on her. Though her father's house had been disgraced in the eyes of all the village by what she had done, though the old man all these years had been bent beneath the shame she had brought upon him, still there was the memory of past kindness and love which he had always shown her. It was true sometimes he had been angry, especially when others had roused him against her and her ways; but always in the end, when she had gone to him, he had forgiven her and taken her back. She would arise and go to her father, and would ask him to forgive her once more; this time in her heart she knew she was in earnest--even if he failed her she would not turn back. Clothed as she was, holding her child in her arms, taking no heed of the spectacle she made, she left the castle, tramped over the ridge and down the valley to Laviano, came to her father's cottage, found him within alone and fell at his feet, confessing her guilt, imploring him with tears to give her shelter once again.

The old man easily recognized his daughter. The years of absence, the fine clothes she wore, the length of years which in some ways had only deepened the striking lines of her handsome face, could not take from his heart the picture of the child of whom once he had been so proud. To forgive was easy; it was easy to find reasons in abundance. Had he not indulged her in the early days, perhaps she would never have fallen. Had he made home a more satisfying place for a child of so yearning a nature, perhaps she would never have gone away. Had he been a more careful guardian, had he protected her from those who had lured her into evil ways long ago, she would never have wandered so far, she would never have brought this shame upon him and upon herself. She was repentant, she wished to make amends, she had proved it by this renunciation, she showed she loved and trusted him; he must give her a chance to recover. If he did not give it to her, who would?

So the old man argued with himself, and for a time his counsel prevailed. Margaret with her child was taken back; if she would live quietly at home the past might be lived down. But such was not according to Margaret's nature. She did not wish the past to be forgotten, it must be atoned. She had done great evil, she had given great scandal; she must prove to God and man that she had broken with the past, and that she meant to make amends. The spirit of fighting sin by public penance was in the air; the Dominican and Franciscan missionaries preached it, there were some in her neighborhood who were carrying it to a dangerous extreme. Margaret would let all the neighbors see that she did not shirk the shame that was her due. Every time she appeared in the church it was with a rope of penance round her waist; she would kneel at the church door that all might pass her by and despise her; since this did not win for her the scorn she desired, one day, when the people were gathered for mass, she stood up before the whole congregation and made public confession of the wickedness of her life.

But this did not please her old father. He had hoped she would lie quiet and let the scandal die; instead she kept the memory of it always alive. He had expected that soon all would be forgotten; instead she made of herself a public show. In a very short time his mind towards her changed. Indulgence turned to resentment, resentment to bitterness, bitterness to something like hatred. Besides, there was another in the house to be reckoned with; the step-mother, who from her first coming there had never been a friend of Margaret. She had endured her return because, for the moment, the old man would not be contradicted, but she had bided her time. Now when he wavered she brought her guns to bear; to the old man in secret, to Margaret before her face, she did not hesitate to use every argument she knew. This hussy who had shamed them all in the sight of the whole village had dared to cross her spotless threshold, and that with a baggage of a child in her arms. How often when she was a girl had she been warned where her reckless life would lead her! When she had gone away, in spite of every appeal, she had been told clearly enough what would be her end. All these years she had continued, never once relenting, never giving them a sign of recognition, knowing very well the disgrace she had brought upon them, while she enjoyed herself in luxury and ease. Let her look to it; let her take the consequences. That house had been shamed enough; it should not be shamed any more, by keeping such a creature under its roof. One day when things had reached a climax, without a word of pity Margaret and her child were driven out of the door. If she wished to do penance, let her go and join the fanatical Flagellants, who were making such a show of themselves not far away.

Margaret stood in the street, homeless, condemned by her own, an outcast. Those in the town looked on and did nothing; she was not one of the kind to whom it was either wise or safe to show pity, much less to take her into their own homes. And Margaret knew it; since her own father had rejected her she could appeal to no one else; she could only hide her head in shame, and find refuge in loneliness in the open lane. But what should she do next? For she had not only herself to care for; there was also the child in her arms. As she sat beneath a tree looking away from Laviano, her eyes wandered up the ridge on which stood Montepulciano. Over that ridge was the bright, gay world she had left, the world without a care, where she had been able to trample scandal underfoot and to live as a queen. There she had friends who loved her; rich friends who had condoned her situation, poor friends who had been beholden to her for the alms she had given them. Up in the castle there were still wealth and luxury waiting for her, and even peace of a kind, if only she would go back to them. Besides, from the castle what good she could do! She was now free; she could repent in silence and apart; with the wealth at her disposal she could help the poor yet more. Since she had determined to change her life, could she not best accomplish it up there, far away from the sight of men?

On the other hand, what was she doing here? She had tried to repent, and all her efforts had only come to this; she was a homeless outcast on the road, with all the world to glare at her as it passed her by. Among her own people, even if in the end she were forgiven and taken back, she could never be the same again. Then came a further thought. She knew herself well by this time. Did she wish that things should be the same again? In Laviano, among the old surroundings which she had long outgrown, among peasants and laborers whom she had long left behind, was it not likely that the old boredom would return, more burdensome now that she had known the delights of freedom? Would not the old temptations return, had they not returned already, had they not been with her all the time, and with all her good intentions was it not certain that she would never be able to resist? Then would her last state be worse than her first. How much better to be prudent, to take the opportunity as it was offered, perhaps to use for good the means and the gifts she had hitherto used only for evil? Thus, resting under a tree in her misery, a great longing came over Margaret, to have done with the penitence which had all gone wrong, to go back to the old life where all had gone well, and would henceforth go better, to solve her problems once and for all by the only way that seemed open to her. That lonely hour beneath the tree was the critical hour of her life.

Happily for her, and for many who have come after her, Margaret survived it: "I have put thee as a burning light," Our Lord said to her later, "to enlighten those who sit in the darkness.--I have set thee as an example to sinners, that in thee they may behold how my mercy awaits the sinner who is willing to repent; for as I have been merciful to thee, so will I be merciful to them." She had made up her mind long ago, and she would not go back now. She shook herself and rose to go; but where? The road down which she went led to Cortona; a voice within her seemed to tell her to go thither. She remembered that at Cortona was a monastery of Franciscans. It was famous all over the countryside; Brother Elias had built it, and had lived and died there; the friars, she knew, were everywhere described as the friends of sinners. She might go to them; perhaps they would have pity on her and find her shelter. But she was not sure. They would know her only too well, for she had long been the talk of the district, even as far as Cortona; was it not too much to expect that the Franciscan friars would so easily believe in so sudden and complete a conversion? Still she could only try; at the worst she could but again be turned into the street, and that would be more endurable from them than the treatment she had just received in Laviano.

Her fears were mistaken. Margaret knocked at the door of the monastery, and the friars did not turn her away. They took pity on her; they accepted her tale though, as was but to be expected, with caution. She made a general confession, with such a flood of tears that those who witnessed it were moved. It was decided that Margaret was, so far at least, sincere and harmless, and they found her a home. They put her in charge of two good matrons of the town, who spent their slender means in helping hard cases and who undertook to provide for her. Under their roof she began in earnest her life of penance. Margaret could not do things by halves; when she had chosen to sin she had defied the world in her sinning, now that she willed to do penance she was equally defiant of what men might think or say. She had reveled in rich clothing and jewels; henceforth, so far as her friends would permit her, she would clothe herself literally in rags. She had slept on luxurious couches; henceforth she would lie only on the hard ground. Her beauty, which had been her ruin, and the ruin of many others besides, and which even now, at twenty-seven, won for her many a glance of admiration as she passed down the street, she was determined to destroy. She cut her face, she injured it with bruises, till men would no longer care to look upon her. Nay, she would go abroad, and where she had sinned most she would make most amends. She would go to Montepulciano; there she would hire a woman to lead her like a beast with a rope round her neck, and cry: "Look at Margaret, the sinner." It needed a strong and wise confessor to keep her within bounds.

Nor was this done only to atone for the past. For years the old cravings were upon her; they had taken deep root and could not at once be rooted out; even to the end of her life she had reason to fear them. Sometimes she would ask herself how long she could continue the fight; sometimes it would be that there was no need, that she should live her life like ordinary mortals. Sometimes again, and this would often come from those about her, it would be suggested to her that all her efforts were only a proof of sheer pride. In many ways we are given to see that with all the sanctity and close union with God which she afterwards attained, Margaret to the end was very human; she was the same Margaret, however chastened, that she had been at the beginning. "My father," she said to her confessor one day, "do not ask me to give in to this body of mine. I cannot afford it. Between me and my body there must needs be a struggle until death."

The rest of Margaret's life is a wonderful record of the way God deals with his penitents. There were her child and herself to be kept, and the fathers wisely bade her earn her own bread. She began by nursing; soon she confined her nursing to the poor, herself living on alms. She retired to a cottage of her own; here, like St. Francis before her, she made it her rule to give her labor to whoever sought it, and to receive in return whatever they chose to give. In return there grew in her a new understanding of that craving for love which had led her into danger. She saw that it never would be satisfied here on earth; she must have more than this world could give her or none at all. And here God was good to her. He gave her an intimate knowledge of Himself; we might say He humored her by letting her realize His love, His care, His watchfulness over her. With all her fear of herself, which was never far away, she grew in confidence because she knew that now she was loved by one who would not fail her. This became the character of her sanctity, founded on that natural trait which was at once her strength and her weakness.

And it is on this account, more than on account of the mere fact that she was a penitent, that she deserves the title of the Second Magdalene. Of the first Magdalene we know this, that she was an intense human being, seeking her own fulfillment at extremes, now in sin, now in repentance regardless of what men might think, uniting love and sorrow so closely that she is forgiven, not for her sorrow so much as for her love. We know that ever afterwards it was the same; the thought of her sin never kept her from her Lord, the knowledge of His love drew her ever closer to Him, till, after Calvary, she is honored the first among those to whom He would show Himself alone. And in that memorable scene we have the two traits which sum her up; He reveals Himself by calling her by her name: "Mary," and yet, when she would cling about His feet, as she had done long before, He bids her not to touch Him. In Margaret of Cortona the character, and the treatment, are parallel. She did not forget what she had been; but from the first the thought of this never for a moment kept her from Our Lord. She gave herself to penance, but the motive of her penance, as her revelations show, was love more than atonement. In her extremes of penance she had no regard for the opinions of men; she would brave any obstacle that she might draw the nearer to Him. At first He humored her; He drew her by revealing to her His appreciation of her love; He even condescended so far as to call her "Child," when she had grown tired of being called "Poverella." But later, when the time for the greatest graces came, then He took her higher by seeming to draw more apart; it was the scene of "Noli me tangere" repeated.

This must suffice for an account of the wonderful graces and revelations that were poured out on Margaret during the last twenty-three years of her life. She came to Cortona as a penitent when she was twenty-seven. For three years the Franciscan fathers kept her on her trial, before they would admit her to the Third Order of St. Francis. She submitted to the condition; during that time she earned her bread, entirely in the service of others. Then she declined to earn it; while she labored in service no less, she would take in return only what was given to her in alms. Soon even this did not satisfy her; she was not content till the half of what was given her in charity was shared with others who seemed to her more needy. Then out of this there grew other things, for Margaret had a practical and organizing mind. She founded institutions of charity, she established an institution of ladies who would spend themselves in the service of the poor and suffering. She took a large part in the keeping of order in that turbulent countryside; even her warlike bishop was compelled to listen to her, and to surrender much of his plunder at her bidding. Like St. Catherine of Siena after her, Margaret is a wonderful instance, not only of the mystic combined with the soul of action, but more of the soul made one of action because it was a mystic, and by means of its mystical insight.

Margaret died in 1297, being just fifty years of age. Her confessor and first biographer tells us that one day, shortly before her death, she had a vision of St. Mary Magdalene, "most faithful of Christ's apostles, clothed in a robe as it were of silver, and crowned with a crown of precious gems, and surrounded by the holy angels." And whilst she was in this ecstasy Christ spoke to Margaret, saying: "My Eternal Father said of Me to the Baptist: This is My beloved Son; so do I say to thee of Magdalene: This is my beloved daughter." On another occasion we are told that "she was taken in spirit to the feet of Christ, which she washed with her tears as did Magdalene of old; and as she wiped His feet she desired greatly to behold His face, and prayed to the Lord to grant her this favor." Thus to the end we see she was the same; and yet the difference!

They buried her in the church of St. Basil in Cortona. Around her body, and later at her tomb, her confessor tells us that so many miracles, physical and spiritual, were worked that he could fill a volume with the record of those which he personally knew alone. And today Cortona boasts of nothing more sacred or more treasured than that same body, which lies there still incorrupt, after more than six centuries, for everyone to see.

Credits to EWTN

Hope you have time to read this three wonderful saints' stories! Enjoy and look for some more saints and posts soon!

God bless,

Mary

No comments:

Post a Comment